Kathmandu : In the Kathmandu Valley, a figure is made in the style of a triangular hole under the main door of the Newar community’s houses, which is called Ajima. It is considered a symbol of the vagina. It is said that since woman’s vagina is worshiped in the Tantra tradition, places and houses that still have ancient civilizations have Ajima figures.

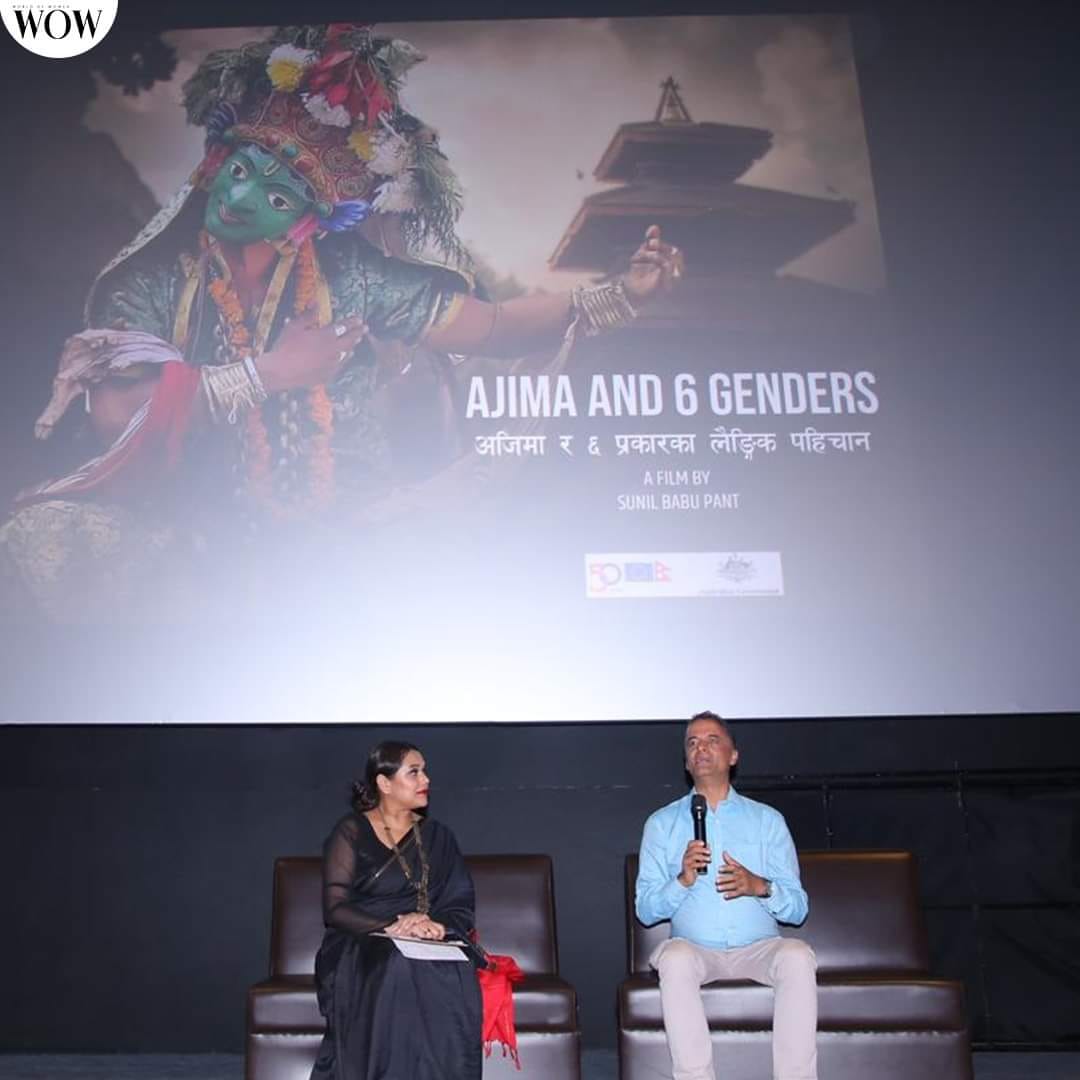

‘Ajima and 6 Gender Identities’ by rights activist Sunil Babu Pant, which was recently premiered at Bishwojyoti theatre in Kathmandu, focuses on the figures, statues and temples of Ajima, exploring matriarchal history. The film has highlighted the complex relationship between Ajima goddesses, the values of patriarchy and matriarchy, the importance given to the vagina by the matriarchy, and the temple of Ajima in the Kathmandu valley.

Although the historical period of matriarchy and patriarchy is a matter of research, Pant says that there is a tradition of worshiping and respecting Ajima goddesses till the era of Lichchhavi dynasty. He says that it is found during the study that the patriarchy gradually took over, sidelining the importance of matriarchy, Tantra and Ajima temples. “As long as the tradition of matriarchy existed, when a child was born, worship was done in the temple of Ajima goddesses. But the patriarchy dominance grew stronger, eradicating this tradition,” says Pant.

He says that during the making of this documentary, it was found that blood at the time of the ending of menstruation is considered sacred. “The first milk of the mother was first offered to Ajima, and the blood of the time when menstruation starts was also considered sacred. After the patriarchy prevailed, menstruation became impure, and the tradition of chhaupadi took place,” he says.

He says that even after the Lichchhavis came to Kathmandu, Ajima was given a special place. After establishing their kingdom in Bhaktapur for the first time, the Lichchhavis built a temple of Ajima around the city. According to him, 10 goddesses were established in Patan as 10 Mahabidhya.

There were temples of Ajima around the old settlement of Kathmandu, which are still known by Matrika, Naradevi, Bhadrakali, Kangi, Pali, Gyneshwori, Panchakumari, Neelbarahi and others. These temples have been featured in Pant’s documentary.

The film mentions that women are not given a place in Hinduism and Buddhism as in the Tantra tradition. Moreover, there are evidences that women are considered the second class people in the mindset of people.

The documentary shows that in Hinduism and Buddhism, the female genitalia is viewed as abomination, but in the Tantra tradition, it is worshiped. “In the Tantra tradition, there is a practice of worshiping the figure of the genitals,” says Pant, “Wherever such figures are seen, it should be considered a Tantric temple.”

Difference between matriarchy and patriarchy

There are two major patriarchal traditions. One is the Shraban tradition of the Sanyasis and the other, the Brahmin tradition of the priests. There is a third but less explored tradition–the matriarchal tradition.

Pant believes that the difference between the spiritual and religious traditions of matriarchy and patriarchy is profound. “Patriarchal practices typically focus on the male deity. “They treat truth as absolute, and suppress the sexuality of women and sexual minorities in particular,” he analyses.

Patriarchy considers women’s bodies impure, and thinks that only men can get salvation. It says that women and the third gender hardly find salvation or it is often impossible for them to get salvation. Brahmin people within the patriarchy seems even more rigid. It says that one should stay away from sensual pleasures.

In contrast, matriarchal spirituality is often based on feminine deities. It accepts human sexuality and embraces sensual pleasures to eliminate internal impurities. Similarly, the Tantra tradition acknowledges women’s sexuality, and places women in a positive role. He interprets the figures of gods and goddesses having intercourse carved on the temple’s tundals (wooden support) as giving equality to gender identity.

The film shows the figures carved in the temples of the Kathmandu Valley, where all genders are seen equal. An example of this is the Ganesh temple at Indra Chowk. Referring to the Ganas of this temple, Pant says, “Even if we look at the old idols in the valley, we find that all genders were accepted in ancient times. Sexuality was not suppressed then, but now there is a problematic situation.”

Similarly, the documentary depicts how the image of the temple’s gajur (pinnacle) was transformed from matriarchy to patriarchy. The structure of the old temple used to have a long gajur. Even now old tantric temples have circular triangular-shaped gajurs. As the patriarchy became dominant, quadrangular or cylindrical-shaped gajurs started to be kept.

“Then, the belief that women have no place in human behavior began to dominate. Gradually, the other sexuality did not also find a place,” says Pant.

More research on Ajima is in need

The documentary has opened the door for further conservation and study on Ajima and sexuality. The film was made after extensive research on Ajima and the Tantra tradition, says Pant, pointing out further study and research on it.

Author and political analyst Bishwobhakt Dulal (Aahuti) comments that as far back in Nepali history, society was more open for women and other genders. “Especially matriarchal society is related to the development of productive power. The more a study on the matter is carried out, the more evidence can be found.”

Scholar and politician Bimala Rai Paudyal says that society is narrowing down on sexuality. Mentioning that today’s society considers women and gender minorities as untouchables, Paudyal says, “From the womb and vagina, someone became a human being. Is it considered impure?” she questions.

Ambassador of Australia to Nepal, Felicity Volk has praised the documentary, stating, “When asked about the image of Ajima, there would be many interpretations. The documentary has opened the door to a conversation about history of Ajima goddesses and Tantra.”

“The documentary has given us a new way to look at the city we love so deeply and I thank you (Sunil Babu Pant) again so much for helping me to see through a more lens.”

EU Ambassador to Nepal Veronique Lorenzo has expressed her admiration for the film, calling it a “feminist documentary”.

“It’s good to be reminded that our societies were not always intolerant and strictly quite patriarchal as it is today. For me, this is a feminist film. It’s wonderful to hear that we do so much work on women empowerment, and this is so much at the center of our agenda, comforting all the women,” she says.

She says that she came to know that in previous ages and societies, women were there and women dominating the society meant more inclusion, more acceptance and just a more comprehensive society.

The next step she thinks is to take this film beyond the Kathmandu valley, and show it to women what their society was many months ago, she suggests.

Copyright © All right reserved to pahichan.com Site By: Sobij.