Kathmandu (Pahichan) April 9 – For the past 15 years fans of tormented superstar Leslie Cheung, one of the first celebrities to come out as gay in Asia, have gathered at Hong Kong’s Mandarin Oriental Hotel to mourn the day he took his own life.

It’s a poignant sign of why the daring and troubled star is still important today.

One of Hong Kong’s most popular male singers and actors of the mid-1980s, Leslie Cheung Kwok Wing was not afraid of provoking controversy with his overt sexuality and provocative performances during a more socially conservative era.

And 15 years after his death, Cheung is still attracting new fans, including teenagers and millennials.

Lam, a 15-year-old who attended 1 April’s vigil, was only a few months old when Cheung died. She told BBC Chinese she had “discovered him on YouTube”.

“He was charismatic; especially when he went androgynous…it’s gorgeous,” she said.

Meanwhile, 25-year-old Wu travelled from Hunan province on mainland China with his boyfriend to mourn the icon.

Wu told BBC Chinese he drew strength from Cheung’s “spirit of being true to oneself”.

“He showed the [Chinese-speaking] world that gay people can be positive, bright and worthy of respect.”

Image copyrightBBC CHINESE

Image copyrightBBC CHINESEBorn in 1956, Leslie Cheung was one of Hong Kong’s most famous stars during the golden era of Cantopop in the 1980s.

He was dashing, stylish and fitted the public idea of a perfect heterosexual male lover. But in reality, he was in a long-term relationship with his childhood friend, Daffy Tong.

It was not an easy time to be gay. At that time, homosexuality was still viewed by many as an illness and abnormality in Hong Kong, especially after the emergence of the first local case of Aids in 1984. It was not until 1991 that adult gay sex was decriminalised in the territory.

“The LGBT movement in Hong Kong took off in the 1990s, when the community finally became visible to the public,” Travis Kong, an associate professor of sociology researching gay culture at The University of Hong Kong, told BBC Chinese.

And it was at this point that Cheung became more daring in his work.

Image copyrightTOMSON (HK) FILMS CO., LTD.

Image copyrightTOMSON (HK) FILMS CO., LTD.He first came to international attention with his portrayal of Cheng Dieyi, the androgynous Peking Opera star, for the film Farewell My Concubine, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1993.

He went on to star in Happy Together directed by Wong Kar Wai – a gay cinema classic about a couple who struggle to find a peaceful co-existence.

“Happy Together is different. It is a stereotypical heterosexual romance, but played by two men,” said Kit Hung, a Hong Kong director.

Meanwhile, Christopher Doyle, the renowned cinematographer who worked with Cheung on various Wong Kar Wai films, told BBC Chinese: “He was so beautiful. We both wanted to convey through my lens the most beautiful, sincerest side of him.

“He enters our imagination audaciously… always showing us better possibilities.”

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

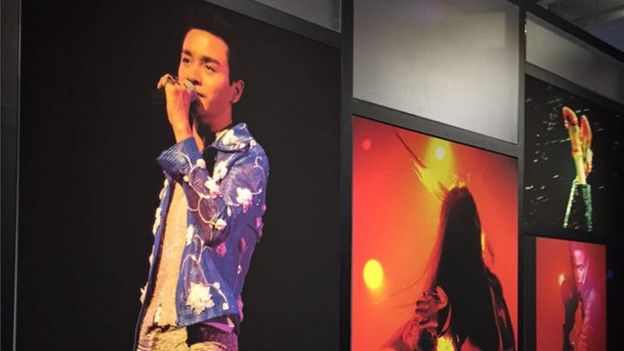

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESOn stage, Cheung unleashed a sexually fluid charm. His defining queer performance came in a 1997 concert where he danced intimately with a male dancer to his song Red. He wore a black suit with a pair of sparkling crimson high-heels.

At that concert he dedicated a classic love song to the two “loves of his life”, his mother and his partner Daffy Tong. This is seen as the moment he came out of the closet. Cheung did not proclaim his sexuality as such, but confessed his love for a man.

Image copyrightROCK RECORDS

Image copyrightROCK RECORDS“In the 1990s, at times a gay man was still called ‘Aids man’ and ‘pervert’,” says Mr Kong. “In a society so oppressive to the LGBT community, the coming out of such a renowned superstar had a huge effect on the general public.”

Despite his success across Asia, there were many who did not appreciate this side of Cheung.

At the 1998 Hong Kong Film Awards, Happy Together was mocked by comedians, who described it as a film that would make the audience vomit. A music video he directed, featuring him topless with a male ballet dancer, was also censored by major local TV channel TVB.

Image copyrightPAN LEI

Image copyrightPAN LEIIn 2000 Leslie became the first Asian star to wear a tailor-made costume by French fashion master Jean-Paul Gaultier in a concert. With waist-length hair, clearly visible stubble and a muscular build, Cheung also wore tight transparent trousers and a short skirt.

He ended the concert with his self-revealing ballad I. “The theme of my performance is this: The most important thing in life, apart from love, is to appreciate your own self,” he explained.

“I won’t hide, I will live my life the way I like under the bright light” he sang. “I am what I am, firelight of a different colour.”

But he was dismissed as a “transvestite”, “perverted” or “haunted by a female ghost” in local media. He would dismiss that criticism as superficial and short-sighted.

He remains such an iconic figure in Hong Kong’s awakening to LGBT issues that the Mandarin Oriental Hotel is even the first stop of a walking tour on the city’s LGBT history.

Image copyrightBBC CHINESE

Image copyrightBBC CHINESE Image copyrightBBC CHINESE

Image copyrightBBC CHINESEIt was from here that he jumped to his death on 1 April 2003 after a long struggle with depression. It was a shocking moment for the city, and a devastating moment for fans.

Tens of thousands turned out to bid him farewell and at the funeral, his partner Daffy Tong assumed the role traditionally preserved for the surviving spouse, a profound, public recognition of their relationship.

Never legally married, Mr Tong’s was the first name listed on the family’s announcement of Cheung’s death, credited “Love of His Life”.

Same-sex marriage or civil unions are still not legal in Hong Kong, but in the city’s collective memory, Cheung and Tong are fondly remembered as an iconic, loving couple.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESHong Kong still lacks anti-discrimination laws protecting LGBT communities but queer identity and sexual fluidity are no longer so taboo and are part of the social landscape.

Last year a museum in Hong Kong held an exhibition “Ambiguously Yours: Gender in Hong Kong Popular Culture”. The first exhibit visitors encountered upon entering the venue was a pair of sparkling crimson high-heels – the pair Cheung wore performing Red in 1997.

“The highest achievement for a performer is to embody both genders at the same time,” Cheung once proclaimed: “For art itself is genderless.”

If you are feeling emotionally distressed and would like details of organisations which offer advice and support, click here. In the UK you can call for free, at any time, to hear recorded information on 0800 066 066. In Hong Kong you can get help here.

Copy : bbc.com

Copyright © All right reserved to pahichan.com Site By: Sobij.