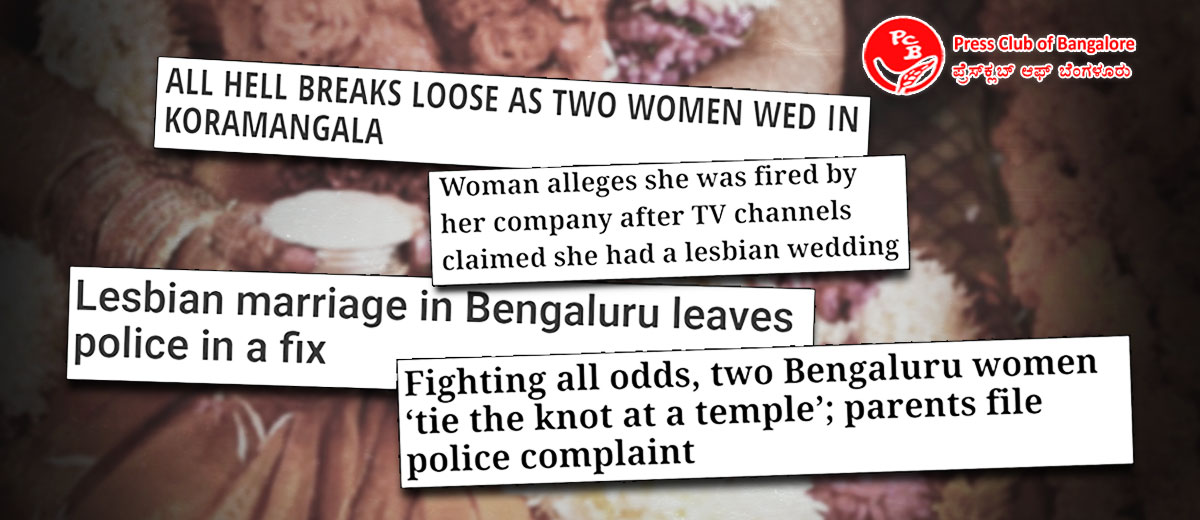

The media, led by the Bangalore Mirror and Public TV, had put out reports stating two women had married each other in “Bangalore’s first lesbian wedding” in a temple in Koramangala. During the meet, activists and lawyers representing the women made it clear that neither of the women actually identified as lesbians, and both women, in fact, deny that they had ever married each other. It was also revealed that one of the women had been unceremoniously and unprofessionally fired over the phone by her employer, gozefo.com, within a few hours of the reports being published.

In the course of a well-deserved and very thorough dressing down, a member of the panel also mentioned in passing that it was extra silly of the media to report their marriage because such a marriage isn’t legally recognised under Indian law.

Oho, well, hold on now. Here is where the logic of that last scolding gets a bit complicated.

India, of course, has a rich, diverse history and cultural tradition of non-heterosexual marriages—which the Bangalore Mirror conveniently forgot about when it decided that Bangalore’s “first” lesbian wedding had just taken place.

Scholars like Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai have already established that same sex marriages have been taking place in India from before colonisation. Writer and queer rights activist Nithin Manayath also wrote in a 2013 piece titled Why marriage equality may not be that equal that hijras and male couples all over India marry each other all the time, and hundreds of hijras marry their lovers in Tamil Nadu’s Koovagam every year. As recently as this April, two women, one of them a police officer, married each other in what appears to be a Hindu ceremony in Jalandhar, Punjab. Several straight, cis people also choose to get married without registering their marriages with the government. All of these marriages and kinds of marriages are certainly worthy of our recognition, if not the law’s.

What these kinds of marriages can do without is the kind of attention from the media such as the first Bangalore Mirror story, which sounded ready to cry that it couldn’t find some way of criminalising the marriage of two women no matter how hard it reached. The report included a lawyer named S. Doreraju’s quote who erroneously claimed that “lesbian marriage is a punishable offence under Section 377” and went on to say almost sadly: “other experts said that since both are adults and nothing has been done in public view, it was very difficult to convict the women of any crime”. It was roughly the same tone as of someone helplessly watching thugs run away with an old lady’s gold chain.

It goes without saying, though, that alternative marriage structures and legality don’t make for a simple or straightforward issue, and comes with in-built internal complications. There’s something important to be said in favour of non-heterosexual marriages remaining outside the purview of the state and legal recognition. For example, as Manayath wrote, if hijras are brought into the legal fold of marriage, as we currently know, it would result in the hijra’s partner having rights over her “marginal savings post her death”, although “hijra’s dharma stipulates that she is to give her wealth to her guru or chelas, not leave it for some man”. And as activist and law professor Gowthaman Ranganathan said, getting the state involved in your marriage also means getting the state involved in your divorce, thus, making it much harder for people in non-traditional marriage structures to leave the relationship when they want to. Alternative forms of marriage currently exist with their own traditions and processes that don’t neatly mirror the form of legally recognised, heterosexual marriages. There’s also the danger that these alternative traditions would be lost if brought under the purview of the state and its definition of marriage.

Of course, there’s also a lot to be said for granting legal recognition to non-heterosexual marriages, such as the financial and social benefits and legitimacy that legal recognition brings.

But the fact is, regardless of whether the law recognises non-heterosexual marriages, and even if we’re not sure we want it to, these different kinds of marriages do exist. They have existed for centuries, they exist today, and they will continue to exist no matter what the stuffy old laws have to say about it. And as people invested in understanding the world and its goings in a varied, rich and inclusive way, isn’t it in our best interest to look beyond the law for what we include as legitimate?

It could also be a useful tool, in the long run, to keep the existence of other forms of marriage in mind for more prosaic, tangible and almost self-serving benefits than just inclusivity. As Manayath demonstrates, alternative marital structures come with their own unique gender norms, traditions, cultures and inheritance structures that are very different from the norms currently surrounding the legally-recognised heterosexual marriages in India. It could be beneficial to us to bring in different facets and features of alternative marriage structures into the way the state and the law understand marriage in general, especially to help reform some of the problematic aspects of heterosexual marriages as we see them today.

That being said, there are still no easy answers or blanket rules. Neither the law, nor existing tradition, can be our automatic go-to when we decide what is legitimate or desirable. The Bhartiya Muslim Mahila Andolan, for example, has been lobbying for years for a complete ban on what might be considered the tradition of triple talaq. The minister for women and child development, Maneka Gandhi, on the other hand, has famously said, “The concept of marital rape, as understood internationally, cannot be suitably applied in the Indian context.”

So neither the law nor tradition can be taken as unchangeable, hard metrics for what we accept as permissible or legitimate. Perhaps fairness, equality, inclusiveness and a lack of harm might be better metrics to keep in mind when we decide what is legitimate and what is not, especially when it comes to marriage. It’s important, especially in these tumultuous times where our little ideological inconsistencies can return to bite us in the ass, to think very deeply about our politics, and to offer discourses that are as kind, inclusive and as resistant to changing circumstances as we can possibly make them.

And if we are not thinking very deeply, perhaps we can offer another metric to apply. Should you report the peaceful union of two adult women on the cover of your newspaper as “all hell breaks loose?” To quote the famous Kannada adage, “No ya, what of your father goes?”

Copy : https://www.newslaundry.com

Copyright © All right reserved to pahichan.com Site By: Sobij.